Hoboken Firehouses and the Firemen's Monument

- Dante Mazza

- Feb 13, 2025

- 36 min read

Updated: 2 hours ago

The Fireman's Monument in Church Square Park in October 2020

Hoboken, New Jersey, is a city full of history.

At only a mile and a quarter square, with a population of just over 60,000, Hoboken does not, based on the numbers alone, sound like it should be one of the most famous cities in the United States. Yet, thanks to proximity to Manhattan, where frequent ferry and PATH train service have transformed Hoboken and the portion of Jersey City immediately to its south into the unofficial sixth borough of New York, the city has had an outsized effect on American arts, culture, and history for almost its entire existence.

Hoboken is known as the first place a real baseball game was ever played in America, the birthplace of music legend Frank Sinatra, the setting for the classic 1954 film On The Waterfront, and, more recently, the home base of the dessert and restaurant empire of "Cake Boss" Buddy Valastro.

Unlike Jersey City to the south, massive new skyscrapers have not overtaken the Hoboken area. Instead, the city mainly consists of low-rise, historic structures packed with shops, restaurants, and apartments. Together, these buildings form a compact and compelling sense of place that helps the small city draw big crowds to live, work, and play.

Such a vibrant atmosphere and beautiful historic environment could not have survived to the present day without protection from one of the gravest threats of earlier times: fire.

Hoboken is home to seven historic firehouses within one-and-a-quarter square miles, most of which are still in use today. Collectively, along with the monument dedicated to the city's volunteer firemen pictured at the top of this post, they have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as significant for their architecture and role in community planning, exploration, and settlement, and politics and government in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Each fire station, built between the 1870s and 1915, has a unique architectural style and helps tell the story of Hoboken.

Hoboken slideshow

Hoboken History: Formed by Fire

The definitive early history of Hoboken seems to have been written by the city's Board of Trade in 1907. The NRHP Nomination form for the firehouses references that publication, pictured above in the Columbia University library's collection.

According to that and other sources, "Hoboken" began as "Hobocan," a native Lenape word for a tobacco pipe. Native inhabitants of the area would use the city, which was then an island, as a source of carvable soapstone, which they used to craft pipes.

European settlement began with the arrival of Henry Hudson, namesake of the river that Hoboken fronts, and his ship, the Half Moon, in 1610. Hudson's voyage led to the creation of what is now New York City, the most populous city in the United States and the global capital of finance, media, art, fashion, and cuisine. Hoboken was a hit from the start, thanks to its prime location just across the river from the city that would become known as the center of the universe.

The first European to own Hoboken was Michael Pauw, who, like his compatriots across the river in Manhattan, "bought" the land from the local native population in 1630. Pauw was Dutch and worked closely with the West India Company, which was responsible for settling New York and the surrounding areas. He eventually ran afoul of his colleagues in the company for not settling the land fast enough, and they repurchased it from him for cash. The area became known as Pavonia, a Latinized version of his name.

Of course, when Pauw had traded a collection of goods to the local Lenape people during his "purchase," they were probably unaware that he was asking them to leave their home forever. When they realized the full extent of the European settlers' intentions, the indigenous people struck back, kicking off a series of bloody battles between the natives and settlers, which the natives initially won. They had control of Hoboken again by 1655.

The Europeans were no strangers to war. They fought plenty amongst themselves, including one which resulted in the area known as New Amsterdam, run by the Dutch, becoming a colony of Great Britain called New York, named for the Duke of York, brother of the King of England, Charles II. The King gave the land to his brother as a gift. The Duke parcelled off the section between the Hudson and Delaware rivers. He granted it to a brother of the Governor of Virginia (another prosperous English colony). He named it New Jersey after the Isle in the English Channel, which had remained loyal to the crown during Oliver Cromwell's time in charge of the UK.

Within New Jersey, Hoboken itself was granted to Nicholas Verlet in 1668. The original deed for the land still survives and was reprinted in the Board of Trade history, as seen below:

Upon Nicholas Verlet's death in 1675, ownership of Hoboken passed through inheritance and marriage from his children to the Bayard family. By the time of the American Revolution, William Bayard owned the land. Like the island for which the state of New Jersey is named, Bayard chose to remain loyal to the English crown, which did not sit well with the Revolutionary-era government of the state, which confiscated all his land and resold it in 1784 to Colonel John Stevens for what was then equivalent to less than $100,000.

Twenty years later, Colonel Stevens opened Hoboken to outsiders for the first time, advertising the sale of 800 lots in 1804. He died in 1838, at which point his heirs established one of the city's most important institutions: the Hoboken Land and Improvement Company, which would oversee the town's explosive growth, starting in 1845 with the construction of homes to attract New Yorkers interested in moving across the Hudson. When the company sold lots, the sale required buildings at least three stories high to be built on them, helping the town proliferate and create density. The company would also be instrumental in connecting Hoboken to the world via ferry and rail service.

One of Stevens' heirs, in particular, would have an essential personal impact on Hoboken. Upon his death in 1868, his son Edwin Augustus Stevens left a significant portion of his land and wealth behind to endow a new institution of higher education. Because the younger Stevens was an amateur engineer, the school had a technical focus. Today, the Stevens Institute of Technology is Hoboken's only university. Founded in 1870, it's one of the oldest technical colleges in the United States, though it now also teaches liberal arts. The school's campus occupies the city's highest natural point, and its principal building, shown below, is named after Edwin Stevens. The school ensures that the name of the founding Stevens family will live in Hoboken forever.

Edwin A. Stevens Hall at the Stevens Institute of Technology is named for the son of Hoboken's founder

A ferry had been running between Hoboken and New York City since the 1770s, but it was well into the 1800s before New Yorkers started making regular trips across the Hudson to Hoboken. At the time, the city was a sort of resort for Manhattanites. The prime draw was Elysian Fields, which the Board of Trade history describes as "a kind of picnic ground where thousands of pleasure seekers enjoyed themselves at the summer gardens and under shade trees which lined the River Walk." In that idyllic space, the world's first baseball game was played on June 19, 1846, as commemorated by the plaque below.

Just one year later, in 1847, Hoboken had its first recorded brush with the scourge of fire. Lightning struck during a fall storm, sparking a blaze that destroyed homes and businesses. Residents wasted no time getting to work. Within a year of the fire, property owners in Hoboken had voluntarily contributed enough money to purchase a fire engine. The New Jersey state legislature formally incorporated the Hoboken Village Volunteer Fire Department on February 28, 1849. Any man between the ages of 21 and 55 was allowed to sign up to serve.

Two fire companies were subsequently formed: Hoboken Fire Company No. 1, also known as Oceana, founded in 1856, and Excelsior No. 2, founded in 1854. According to the official Hoboken Fire History on the city's website, "Both headquarters sat side by side on the corner of Washington and Sixth streets." The nomination form describes that long-since demolished firehouse as "a two-story corner building, with four window bays along the Washington Street facade" and "paired, arch-headed windows centered over the engine doors," plus a fire watch tower on top.

Later, a new purpose-built firehouse was constructed on Market Square, the current site of City Hall. The nomination form describes the building as a "two-story brick firehouse" with "a bracketed, Italianate cornice and arched, shuttered upper story windows, centered over the engine doors," and a detached wooden watch tower built on the roof.

A third company, Fire Company No. 3, "Meadow," was formed to cover the city's western section and was housed in the building on Park Avenue mentioned below.

Between the incorporation of the Fire Department and the incorporation of Hoboken on March 28, 1855, via another act of the legislature, there were two more significant fires in town: one in the main section that destroyed four homes and another up on Castle Point, where the Stevens Institute now sits, that destroyed the Stevens Villa.

When the city's incorporation arrived, its charter included provisions related to fire response, all tied to population. It authorized one fire engine company of up to 50 men for every 3,000 residents, and one hook and ladder/hose company of up to 25 men was allowed for every 6,000 residents. At the time of incorporation, Hoboken had fewer than 7,000 residents. In 50 years, the population would multiply tenfold. By 1905, there were 65,000 residents, more than today.

The next major event in Hoboken's firefighting history was the formation of the Assembly of Exempt Firemen in 1860. The nomination form describes it as "a group formed to assist the volunteer firefighters of the city" in the days before a professional, paid force. Today, the group is one of the chapters of the New Jersey State Exempt Firemen's Association, a unique organization that combines elements of a charity, fraternity, and union, advocating for and caring for firefighters who have served for at least seven years. The hall eventually built to host the group is the second firehouse featured in the next section.

The 1860s was also a significant decade for technological development. Hoboken's public water system came online, using wooden water mains that could be tapped by boring a hole. The city's official fire history recounts, "Each pumper carried a short pipe that could be pushed into the hole to deliver water to the pump." Steam technology also spurred the creation of new fire engines: "splendid creations with large spoked wheels and shiny metal work" that were "horse-drawn, in a three-abreast hitch, creating a spectacular sight as they raced to the fire."

Edwin Augustus Stevens and his experimental engineering led to another major fire in Hoboken's history. Stevens and two of his brothers contracted with the federal government to build a "shot and shell-proof" ship, which would later become known as an ironclad. The nomination form states, "The project was doomed by political problems in Washington, D.C.," which appear to be funding-related issues. Nevertheless, the Stevens brothers were able to build a massive ship known as the Stevens' Battery, which, in many ways, was ahead of its time. So far ahead, it was never actually put to use; instead, it was "a sight on the Hoboken waterfront for many years, until its eventual dissolution." The area around the ship's drydock caught fire in 1863 amid the Civil War, and three bomb shells exploded during the blaze. That same year, the Carpenter Brothers lumber, lime, cement, and brick works at the foot of 3rd St also caught fire.

As Hoboken made the century-long shift from a nature-focused town centered on Elysian Fields to an industrial port city that served as a backdrop for On the Waterfront, fire became a fact of life.

In 1864, Montague's feed store went up in flames. In 1866, fires broke out at Cardner & Harp's lumber yard, Schuhler's furniture store on Washington St, and a local tavern. In 1868, there was a blaze at the Roman Cottage Shades Company. In 1872, a fire destroyed five houses on First St. between Madison & Monroe. In 1873, it was the Busch Hotel that got burned. That same year, 25 members of Hoboken's Company No. 1 used the local railroads to travel to the nearby town of Newton and helped extinguish a large blaze there after a request for assistance came in by telegraph. In 1874, Muller's woodworking plane mill and six surrounding buildings were all destroyed by flames. 1876 was the year of the Simley shoe store fire.

Hoboken's oldest extant firehouse was constructed in the 1870s. Located at 212 Park Avenue, it is the first firehouse described in the next section and the only one that represents the old (1840s-1870s) way of building firehouses in the city: built completely flush with and in the same style as all the other rowhouses on its block. The building looks so residential that it has long since been decommissioned as a firehouse and remodeled into a private residence for a single owner. This firehouse was home to the "Meadow" company.

Next on the construction list was the firehouse on Bloomfield Street, which, as mentioned above, became the home of the Assembly of Exempt Firemen and served as the Hoboken Fire Museum until it shuttered due to insurance issues. All the remaining firehouses described individually in the next section are still in use today and serve the people of Hoboken.

By 1880, Hoboken's population had grown significantly since incorporation, reaching 31,000. More people meant more industry and, of course, more fires. The decade began with yet another blaze at the Stevens property on Castle Point, where the Institute of Technology now stands. A fire at the Francis Lumber Yard followed that up. In 1881, flames destroyed Eagle Dock. In 1882, Muller's competitors in the woodworking plane mill industry, Gahagan & Son, also got hit with a fire.

Hoboken's City Hall stands across the street from Carlo's Bakery, of "Cake Boss" fame, on the site of one of the city's earliest firehouses. In the preceding decade, the architect of City Hall also designed the second-oldest firehouse in town, the Assembly of Exempt Firemen building.

Hoboken's current City Hall opened in 1883, replacing Market Square and the location of the city's original firehouse. The building was constructed after the State legislature passed an 1881 law requiring municipalities to erect city halls. The city had been renting office space but decided to build on land deeded by the Hoboken Land & Improvement Co. on Market Square. To design the new building, Hoboken called on local architect Francis G. Himpler, who had designed the Assembly of Exempt Firemen building in the 1870s. He would also create the Church of Our Lady of Grace, another NRHP-listed structure that faces the park in which the Fireman's Monument now stands.

While building City Hall, the Hoboken government also built a new firehouse on Washington Street between 13th and 14th to serve the piers along the waterfront in that part of the city, where there is still an active ferry stop.

The parade of fires continued along with the new construction. In 1884, the Klein Wagon Works caught fire. The following year, some residential structures on a block of 1st Street rose in flames. In 1886, a fire destroyed the F.G. Machler Furniture Co. The 14th Street ferry mentioned in the prior paragraph began service that same year. There was a residential fire on Bloomfield Street in 1887. In 1888, a fire destroyed the firehouse built on Washington Street near the new 14th Street ferry.

1889 was the year of the paper mill fire. 1890 saw both fires at the German Club and a cork factory, plus the construction of the current firehouse at 1313 Washington Street, home to Engine Company No. 2, the third firehouse covered in the section below, replacing the one by the ferry, lost to fire in 1888. In 1897, just seven years after the new firehouse's construction, the block immediately to its south was engulfed in a factory fire that destroyed apartment buildings.

In 1865, under pressure from the citizenry and the insurance industry, New York City abandoned its long-standing but notoriously rowdy volunteer fire companies in favor of a permanent professional force that operates today as the celebrated FDNY. Hoboken followed suit in 1891, switching to a professional force now known as the Hoboken Fire Department. Yet, the city did not forget the heroism of its volunteer firefighters. On May 30, 1891, less than a month before the establishment of the department, citizens gathered in Church Square Park to lay the cornerstone of the Fireman's Monument with a silver trowel. They placed Badge No. 222 and the members' names, written on parchment, in a box underneath it. The memorial is inscribed with the date of the ceremony and the dedication to the volunteers, as shown below.

The creation of a professional force led to the rapid physical expansion of the fire department. In 1892, another firehouse, the fourth in the next section, was built on Observer Highway. Another firehouse was built in 1894 but was destroyed in 1975 and replaced by a bank branch with a drive-thru. The existing firehouse at 415 Grand Street, fifth in the section below, came just four years later, in 1898.

As firehouse construction continued, so too did the fires. The 1900 fire was one of the city's most destructive, so infamous in history that it has its own Wikipedia page. Over 300 people died when a supply of cotton bales stored on the pier caught fire. The blaze destroyed the German ocean liner SS Saale. The captain and many passengers perished in the flames. Four years later, 13 people were killed in another Hoboken fire that engulfed four homes. There was also a factory fire. In 1905, a ferry boat caught on fire and spread the flames to the ferry and rail terminal, destroying it and a nearby restaurant.

Firehouse construction continued apace to keep up with the enormous blazes. In 1907, the brick firehouse on the corner of Clinton and 8th streets, the second-to-last in the section below, was built. One year later, President Theodore Roosevelt pushed a button in the White House that lit the electric lines powering what is now the PATH train service between Hoboken and Manhattan. This link would later be critical to the city's growth.

In 1915, the firehouse at Jefferson and 2nd Streets was constructed. Still in use today, it currently operates as the headquarters of the Hoboken Fire Department. 1915 was also the birth year of Hoboken's most famous native son, Frank Sinatra. Ol' Blue Eyes came into the world in a rather dramatic fashion in a since-demolished tenement on Monroe Street. Frank weighed in at an astonishing 13.5 pounds, and doctors had to bring him into the world with forceps. The procedure ripped his face, neck, and ears, leaving lifelong scars.

Two years later, WWI was underway, and Hoboken was at the center of the action. President Woodrow Wilson designated the city as the embarkation point for all American troops, known as "doughboys," bound for Europe. It was a somewhat ironic choice. Until then, Hoboken had been a very German city, and its piers were the final destination of the significant German ocean liners crossing the Atlantic. Many Germans fled, and Hoboken became a government town. As the troops shipped out, their leader, General John Pershing, predicted that by Christmas, everyone would find themselves in either “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken." It remained a rallying cry for the rest of the war.

Pershing presented a seemingly binary choice, but some doughboys presumably got to more than one of his predicted destinations. Plenty came back to Hoboken in coffins. Five thousand seven hundred ninety-five coffins had returned from France for burial and were stored on Hoboken piers when an electrical fire broke out in 1921. A request for assistance from New York went out over the wireless telegraph while Army soldiers and civilian volunteers moved the coffins to safety. A fireboat from New York arrived in time to help fight the blaze and saved the Army transport ship Leviathan from burning.

The pier fire could have spurred the next advance in Hoboken firefighting technology when, according to the nomination form, "the US Government offered Hoboken a fireboat with the provision that the city absorb the costs of maintaining it and the expense of crews to man it." But instead, "The city declined to accept the offer, leaving the waterfront under the protection of land-based operations."

By the time WWII broke out in Europe in 1939, Hoboken had fallen victim to the historically shameful process of redlining. During the Great Depression, Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to prevent homeowner defaults by purchasing mortgages in exchange for bonds and providing cash advances for taxes and repairs.

To carry out the program, the corporation created maps of neighborhoods divided into four categories, supposedly based on the financial risk level of the mortgages. Later research revealed that the corporation's maps heavily emphasized the racial makeup of each neighborhood. Inspectors gave areas with high numbers of nonwhite residents or recent immigrants the lowest rating, a D, and colored them red on the maps. This practice is where the term "redlining" originates.

In America at large, redlining made it nearly impossible for Black citizens to buy homes or move. In Hoboken, Italian immigrants faced similar discrimination. Sections of the city were condemned to become slums, owned by profit-driven landlords, not families seeking to build wealth through property and live in safe, modern homes. This situation set the stage for future fire risks.

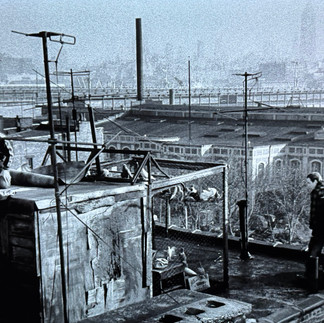

The 1954 film On the Waterfront portrays Hoboken's gritty, industrial nature following the effects of redlining. The American Film Institute has ranked it the 19th greatest movie ever. The film features a haunting score by Leonard Bernstein. It stars Marlon Brando as a longshoreman who aims to upend his industry's corruption. Shot in Hoboken, the film reveals the condition of local housing in scenes where Brando tends to his pet pigeons on his apartment building's roof, as shown in the gallery below.

Hoboken on display in "On The Waterfront" (1954)

Around the same time as the film's release, Hoboken made significant advances in firefighting technology, implementing the centrifugal pump and the 100-foot hydraulic-lifted steel aerial ladder. High-rise fires could now be fought 100 feet in the air at 1,000 gallons per minute, and that capability would soon be tested.

On the Waterfront captured a pivotal moment that was nearing its end. The 1960s saw the introduction of shipping containerization, with ships arriving at port carrying goods pre-packed in large metal containers that cranes could swiftly transfer to semi-trucks or freight trains. The demand for longshoremen drastically decreased. Hoboken faced challenges as shipping operations shifted to the container ports in Bayonne, Newark, and Elizabeth, leading to economic and population decline. Factories continued to provide employment, appealing to recent immigrant communities, particularly from Puerto Rico. During this period, Hoboken evolved into a city with strong Italian and Puerto Rican communities, reminiscent of the setting in West Side Story.

FDR's New Deal program had redlined Hoboken. LBJ's Great Society program would be responsible for undoing the damage through gentrification, another blow to longtime residents. Out of the War on Poverty came the Model Cities Program, which itself begat the Home Improvement Program, which proved very popular in Hoboken. According to the Hoboken History Museum:

"The city allocated public funds into subsidies for low-interest mortgages for brownstone purchases, targeting middle class people from outside Hoboken, mainly from the New Jersey suburbs. These new 'adventure seekers'—or 'pioneers,' as they were dubbed by the media—were now able to obtain mortgages at a 3% interest rate as opposed to the 9% standard national rate."

This view of the New World Trade Center from a street near Hoboken's PATH train station reveals how short the commute to Lower Manhattan is for the city's residents. The construction of the original World Trade Center with a PATH station in the middle during the 1970s helped spur an influx of young professionals from the financial industry and Hoboken's gentrification.

In 1975, the Great Society programs in Hoboken were consolidated under the Community Development Agency of Hoboken, a public-private partnership. While early efforts to rehabilitate Hoboken focused on providing high-quality, affordable housing for longtime residents, the model eventually shifted to the much more profitable process of gentrification. The Community Development Agency was responsible for attracting young urban professionals to Hoboken who worked in Manhattan's fast-growing financial sector, best symbolized by the 1974 opening of the original World Trade Center, which had been constructed with a PATH train terminal right in the middle of it, allowing for a nearly seamless commute from Hoboken.

The Community Development Agency helped market the city through historic preservation. As a 1976 article in the New York Times explains, "At 84 Washington Street, Community Development Agency pamphlets providing an annotated walking tour will be available to tourists after May 17. On that day, the historic sites committee of the Hoboken Bicentennial Commission will officially mark the beginning of that program with guided tours." The article points out two historic sites already listed on the National Register: the train and ferry terminal and City Hall.

The effort to identify and promote Hoboken's historic landmarks continued with the 1977 listing of the Church of the Holy Innocents and the 1979 listing of the Hoboken Land and Improvement Company Building, which reflected the company's significant importance to the city's history. Then, the Community Development Agency set its sights on a complete collection of historic buildings to list all at once: Hoboken's historic firehouses.

The Nomination Form explains, "The initial identification of the sites was made as part of a city-wide historic sites inventory begun by the Community Development Agency of Hoboken in 1978 with a grant from the State Historic Preservation Office. The concept of nominating the structures originated in 1981 and is now being completed as a thematic group." Ironically, just as the Community Development Agency recognized the fire stations for their historic value, the same agency's actions ensured they were used more than ever.

Fire still had one more pivotal role left to play in Hoboken's history, but this time, it would be arson, not accidents, that scarred the city. On January 21, 1979, Hoboken was rocked by an apartment fire at 131 Clinton Street that left 22 people dead, including 14 children. Almost 150 other people were either injured in the blaze or displaced from their homes. Authorities accused the building's owner of arson, but she denied the charge, and no further investigation was launched. Nevertheless, the Hoboken History Museum marks the incident as "the beginning of the 'arson for profit' epidemic that would consume the city."

The arson-for-profit system was as simple as it was vile. Owners could drive out rent-controlled tenants with fire damage, collect insurance money, renovate or rebuild, and charge new tenants with jobs in Manhattan's Financial District, who pay rents several times higher than those paid by the original, displaced tenants. One measure passed by the Hoboken City Council made arson even more attractive: it allowed landlords to immediately shift rent-controlled apartments to the market rental rate the second a rent-controlled tenant vacated the unit. There was no faster way to get out rent-controlled tenants than flames and smoke.

As the 1980s arrived, the arsons only got worse. Dozens of families were displaced over just a few months as their buildings suspiciously went up in flames. One of the worst fires was on Park Avenue, just a couple blocks south of the city's oldest firehouse. Two young boys were found dead in their apartment's bathtub after firefighters extinguished the blaze. Their mother and sister had survived only by jumping from a third-story window.

Fire after fire haunted the city, almost all in buildings near the PATH train into Manhattan. As one resident told a local newspaper, “I can’t sleep at all. I’m too afraid that my daughter and I will die just like what happened on Park Avenue.” According to one detailed article in the Journal of American History, nearly 500 fires broke out in Hoboken between 1978 and 1983. Some 7,000 Latino residents of Hoboken left the city throughout the 1980s. Hoboken's historic firehouses were being put to the ultimate test.

Eventually, however, the fires grew so numerous and destructive that they could no longer be ignored or dismissed as mere accidents. Local newspapers and television stations started covering the blazes and their significant human toll on the community. Tenants of affected buildings or those who thought their homes could be targeted next organized for their rights, sometimes joined by the "pioneers" who had purchased brownstone homes at the beginning of gentrification.

Changes in public policy also helped end the arson epidemic. Hoboken's previously industrialized waterfront was opened to residential development, allowing for the construction of new condo buildings without the need to displace anyone. Neighboring Jersey City's PATH stations made new, large-scale development easier, transforming its waterfront area into a canyon of skyscrapers filled with Manhattan commuters. Congress held hearings on the arson-for-profit system and passed the Anti-Arson Act, which made investigating arson a higher priority for the FBI. In 1985, anti-development candidate Thomas

Vezzetti was elected Mayor of Hoboken with the support of many fire victims. Around this time, the city also passed a smoke detector ordinance that later became the model for a statewide version.

The arson ended, but it had its intended effect. Hoboken was a different city after the blazes, the one it is today, stocked with urban professionals, many of whom commute into Manhattan daily. Even as the city writ large moved on from the memory of the fires, a committed community has never forgotten their impact. The arsons have been the subject of scholarship, museum exhibits, and documentary films. In 2022, a plaque honoring the victims was installed in a Hoboken park.

The seven historic firehouses were listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 30, 1984, and the Firemen's Monument joined them in October 1986. Since then, Hoboken's leaders have taken a great interest in historic preservation, continuing to list landmark churches, synagogues, libraries, and buildings at the Stevens Institute on the National Register.

Thankfully, fire no longer determines the history of Hoboken. The historic stations operate well enough in modern times to keep up with today's firefighting demands. But each is unique and tells a story integral to the city's history. Read on for a complete description of each firehouse.

212 Park Avenue

(Formerly Engine #4)

This building, now a private home, is considered the oldest surviving firehouse in Hoboken and was built in the 1870s. While elegant, the old station does not stand out much from the other buildings on the block. It blends in rather well, reflecting the days when firehouses were built for purely practical purposes rather than as statement pieces reflecting civic pride. dating back to the 1840s. The nomination form says this firehouse was "principally geared toward accommodating the hand-pumped steam engines, which were dragged to the scene of fires by the firemen." Despite its emphasis on practicality, the building does still have some notable architectural details, as reported in the nomination form and displayed below:

"Arched brick window lintels terminate in raised brick foliated ornamented blocks/brackets and windows with arched heads. The arched brick lintels and their ornamentation suggest a vernacular Italianate influence."

"The ground floor fluted cast-iron piers frame a single engine door, flanked by a window to the south and a door to the north."

"The cornice was removed at an indeterminate date, leaving raised brick support arches below the parapet. This suggests that the cornice originally in place followed the arches and may have been ornamented with foliate brackets. The second-story brick piers are accentuated by a molded fascia."

"The identifying sign/plaque of the firehouse spans the entire facade

horizontally, and projects at either end to follow the brick piers of

the north and south sides of the facade."

Faint vestiges of whatever was written on the identifying sign/plaque are still visible upon close examination.

Another notable feature of this firehouse is its location, described in the nomination form as mid-block on a side street. It's not even set back from the street any more than usual. Almost nothing sets it apart from the other buildings along what is now called Park Avenue but was initially named Meadow Street, given its proximity to the salt marsh area on the city's outskirts, one block west. The company based here was known as the "Meadow Company" in the early days of the Fire Department.

The nomination form gives the following statement of significance for this former firehouse:

"This building represents a tangible link to the fire-fighting history of the city, but alterations have compromised its architectural |integrity. The finding of National Register eligibility for the structure would hold out the possibility of its future restoration, while providing a developmental context within which to view the other houses."

The building was indeed found eligible and has since enjoyed a new life as a private residence.

Assembly of Exempt Firemen

The Assembly of Exempt Firemen Hall at 213 Bloomfield Street was built in the 1870s as a meeting house for the Exempt Firemen, which had been formed in the prior decade. The nomination form describes it as "a group formed to assist the volunteer firefighters of the city" in the days before a professional, paid force.

Hoboken architect Francis George Himpler designed the building in the late Italianate style. Himpler would go on to create the Hoboken City Hall and Our Lady of Grace Church, and according to the nomination form, "was an architect of statewide prominence." Like many in Hoboken at the time, Himpler was originally from Germany but made the city his second home. The nomination form says he "was fluent in the Second Empire Style and the Gothic Revival styles as well" and that "in his later work especially, such as his home on Lake Hopatcong, this combination of the Italianate and Second Empire styles is melded with the influence of the Renaissance Revival most successfully." The form calls the Assembly Hall "a seminal example of this eclecticism."

Like the decommissioned firehouse on Park Avenue, the Assembly Hall sits mid-block on a residential street amid buildings of similar height. What's different is the elaborate architectural design of the firehouse, largely dispensing with the vernacular style of the Park Avenue station. Past firehouses had been built exclusively with practical realities in mind. A large door was needed at the base of the building for a fire engine, and office or dormitory space above for the firefighters. The nomination form calls the Assembly Hall a building that was "the first which displayed a studied approach to the design of such a structure" and says it "features an eclectic approach to setting the building apart from its neighbors while retaining the three-story height and standard width."

Here are the features that give the Assembly Hall its "architectural distinction":

"The principal facade material is brick, with brownstone trim and what may be limestone trim."

"Central segmentally-arched engine door with molded brick trim. The engine door aperture is arched and carries decorative insignia. Lancet window to the south of the engine door and pedestrian door to the north."

"Centered above the engine door is a grouping of three, equally-sized one-over-one, arch-headed windows with segmentally-arched lintels and ornamented keystones."

"Centered above the second-story windows is a grouping of three lancet windows at the attic story level.

"The central portion of the facade terminates in a pediment with wood modillion blocks that suggest other stylistic influences."

The Assembly of Exempt Firemen building is one of the most significant firehouses in Hoboken, as it is one of the city's oldest, a symbol of the Exempt Fireman association, and the first architecturally elaborate firehouse in the city, setting the standard for future stations. It is also the work of a prominent local architect. The building housed the Hoboken Fire Museum for many years until it was eventually shuttered over insurance issues. Though not an operating firehouse today, the building is kept in remarkable condition and is a beautiful tribute to the firefighters of Hoboken. It has been well preserved by its listing on the National Register, represented by a plaque mounted on the facade.

Each remaining firehouse in this section is active and operating today.

Engine Company No. 2

Engine Company No. 2 is the northernmost firehouse in Hoboken, strategically located near the corner of Washington and 14th streets, less than three football fields' length from the Hudson River. The Fletcher Company once manufactured steamship boilers and engines along the shoreline, and the 14th Street Ferry has operated from a nearby pier since 1886. A firehouse has been near this location since 1880, but the original ironically burned to the ground in 1888 during a large fire. This current building is the replacement, built on land donated by the Stevens family.

Built in 1890, this firehouse was designed by French Dixon & DeSaldern in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, uncommon in Hoboken. The nomination form calls it an "architectural statement" with the following key features:

The building is made of tan stretcher bond brick with carved brownstone coursing. These fire-resistant materials help ensure the firehouse doesn't suffer the same fate as its predecessor. As seen above, the name of an Assistant Engineer is engraved on the building.

"The fire engine door is flanked by cast-iron pilasters, set in rough-hewn brownstone blocks, which carry brownstone half-columns with foliate capitals. The widening of the engine door aperture and the installation of a new door occurred in the early 1970s, an alteration which caused the removal of one cast-iron pier and glass transoms directly above the former door."

"The window centered above the engine door at the second floor is flanked by stout brownstone pilasters which appear to bear the piers separating the transoms."

The third-floor level includes several intricately carved embellishments and an arch-headed window at the center. The arch over the window is a prime example of what the nomination form calls "deliberately rough-hewn brownstone arches and half-columns, which have an antique quality." Arches are almost mandatory in the Romanesque Revival style, so including one here clearly marks this fire station as "stylistically unique," one of the few public buildings in Hoboken, with such a strong influence of the architect H.H. Richardson."

The "weathered limestone plaque at the third story level" originally had the construction date engraved on it but now features a golden eagle.

This particular firehouse marks an essential moment in Hoboken's firefighting history. It was the first time the fire tower was integrated into the overall design scheme of the city's firehouses. Previous fire towers had been standalone wood additions on top of a station's flat roof. The tower's circular window is one of the station's defining features, but likely does not get much use today. Modern firefighters don't need to look out from a tower to be alerted of fires.

The aforementioned "circular window in the tower" sits just below the station's "roof of orange pantiles"

A chimney on the northern wall serves an obvious practical purpose but also balances nicely with the tower on the southern end of the roof.

"The fascia and letters identifying the building as Engine Co. No.2 are original to the firehouse."

Overall, the nomination form calls this fire station "a fine example of the level of craftsmanship and design ability available locally in the 1890s" and "one of the first group of public buildings undertaken by the city to be a self-consciously architectural statement." At the time of its nomination, it was also "the only building in Hoboken to have been recorded (photographically) for the Historic American Buildings Survey."

Engine No. 2 is also noticeably set back some 12 feet from the other buildings on its block. According to local lore, that choice was made to protect pedestrians walking to and from the nearby 14th Street ferry from tobacco-spitting firemen.

The Fireman's Monument

In June 1891, the city of Hoboken established a paid, professional fire department to replace what had been an all-volunteer force. The outgoing volunteer firemen were not forgotten, though. Quite the opposite. They were afforded a rare public honor: this monument, dedicated in Church Square Park in the heart of the city on May 30, 1891, and erected by the citizens of Hoboken.

According to the nomination form, a special committee had been set up to obtain a silver trowel for laying the monument's cornerstone. The effort was successful, and on Dedication Day, "Badge No. 222 and the names of members, written on parchment, were ordered placed in a box under the cornerstone" as a further tribute to the men who had spent decades battling the city's blazes.

The monument was dedicated near the height of the popularity of cast iron, which had exploded with the Industrial Revolution to be found in and on buildings and bridges everywhere, including across the river in Manhattan, where the SoHo neighborhood to this day has one of the world's largest and best-preserved collections of cast iron architecture. It's no surprise then that the New York firm of J.W. Fiske created the statue atop the monument. Though the monument is cast of bronze, not iron, it fits into the tradition of its time.

Until now, public statues in America were usually reserved for larger-than-life national heroes like General and President Andrew Jackson. In the years following the Civil War, however, interest grew in honoring the ordinary soldiers who had fought on either side. Yet, even these monuments seemed to trend toward grandeur, as in nearby Brooklyn's Soldiers' and Sailors' Arch, which went up around the same time.

What makes the Firemen's Monument unique, both in its time and today, is its ordinary subject. Volunteer Firemen were local heroes but did not fight in history-changing wars. Their names were unknown in history, and their good deeds did not come at places like Gettysburg. They were everyday men, known only to their neighbors, the people they helped the most, and gaining no further recognition for their deeds than perhaps a write-up in the local newspaper. Yet, this monument was the community's way of honoring these everyday heroes in public and for all time. The nomination form calls the memorial and others like it "the first public commemorative to the common man; not an imaginary, mythical figure or a famous character, but a real person."

Despite the noble intention of publicly honoring local heroes, monuments like this are relatively rare. According to the nomination form, "Generally, in New Jersey, only the more urban centers of the state erected monuments dedicated to firemen prior to 1920, and only a few were cast-metal firemen's statues." The only other significant example in the state stands in front of City Hall in Trenton, the state capital, as seen below.

A Firemen's Monument, very similar to the one in Hoboken, stands in front of the City Hall in Trenton, New Jersey, honoring that city's paid and volunteer firefighters

Once again, Hoboken's immediate proximity to New York City likely helped it obtain a unique feature far beyond what another city of similar size and population would boast. That's because the New York cast metal firm J.W. Fiske used the dedication of the statue as an occasion to advertise its services right in the program of the dedication ceremony:

"An advertisement appearing in the souvenir programme for the Decoration Day event pictured a drinking fountain, upon which a version of the Firemen's Montiment was placed. The advertisement states that "The Fireman shown on this Drinking Fountain is the same as the one furbished the Fire Department of the City of Hoboken, N.J. Special inducements offered to cities contemplating erecting Firemen's or Soldiers' Monxunents in either Standard Bronze or Zinc."

The design is simple:

A bronze life-sized figure of a fireman in full uniform is holding a lantern

in one hand...

...and a small child in his other arm, whom he is symbolically rescuing from a fire. Note also the words J.W. Fiske engraved at the base.

The bronze statue stands atop a marble base with relief sculptures of a hook, ladder, and hose, the key equipment of firefighting and the basis for fire company names (hook and ladder or engine)

Since it was added to the National Register later than the firehouses, the nomination form gives the Monument its own statement of significance:

"Because of its rarity in New Jersey, artistically, the Hoboken Firemen's Monument is an important, although mass produced, example of a typical decorative public art form popular during the late 19th - early 20th centuries. According to noted cast-iron authority Margot Gayle, cast-metal firemen's statues are relatively uncommon and the Hoboken Firemen's Monument is especially valuable because it was produced by J.W. Fiske Company of NY, a major manufacturer of cast iron ornament in the last half of the 19th century"

Engine Company No. 1/Truck Company No. 2

In 1894, the first free-standing firehouse in Hoboken opened on a triangular plot of land formed by the intersection of Madison Street, Newark Street, and Observer Highway. This is the southernmost fire station in Hoboken, with the city limits terminating at the railroad tracks just a block south. It's the home of Engine Co. #1 and Truck Co. #2.

Engine doors face two of the three streets, allowing easy access to every part of the city.

According to a plaque mounted near one of the engine doors, the project began with a 1892 dedication ceremony presided over by Mayor Edward Stanton. Local architect Charles Fall designed this station, like Engine No.2, in the Romanesque Revival style, but the nomination form says it's a "more domesticated" example. There have also been significant alterations to the exterior over time. Nevertheless, the nomination form gives the design high praise, including the declaration that "from the time of its construction, up until 1915, it was the most grand and impressively-scaled of the Hoboken firehouses." Architect Fall is also said to have "successfully exploited" the "special type of importance" the building was granted by its position on a prominent corner of a central commercial corridor.

Here are some of the architectural details that help the station stand out:

A fieldstone granite foundation

Walls of orange-brown moulded brick with sandstone trim

The nomination form describes "a carved decorative series of fascias," but they appear to have been covered up in the decades since the nomination.

Instead, the most elaborate detail comes at the ground level with the Romanesque style's trademark sandstone arch.

Like its contemporary Engine No. 2, this station also featured a built-in fire tower. Initially, the tower "terminated in a pyramidal slate roof."

"The area between the third story level and the roof was treated as a Romanesque arcade to suggest a belvedere," as seen here in the large arches under the triangular roof peaks.

While the nomination form concedes that alterations have degraded the station's architectural significance, it maintains that its historical importance remains intact: "Its prominent corner location, apart from its functional aspects, also underscores the importance of the firehouse—a symbol of security and municipal planning—laced at a gateway area of the city."

The plaque mentioned at the beginning of this section gives the year of dedication.

Engine Company No. 5

As Hoboken grew, the need for new firehouses to protect property and lives increased. The salt marsh for which the Meadow Company had been named was filled in and built over in the 1880s, expanding the city and adding more structures that needed protection. In the 1890-91 Hoboken Fire Department Annual Report, Chief Engineer Ivins D. Applegate wrote: "The third ward is now entirely without protection against fire, as there is no company west of Washington Street nor north of Third Street. Therefore, I would again require the erection of an engine house in the neighborhood of Fifth or Sixth and Grand or Adams Streets and that a steam fire engine, hose wagon, horses and harness, and company of firemen be placed in said house."

Located on Grand Street between 4th and 5th, this 1898 Engine Company No. 5 answers his request. It also marks a departure from the Romanesque-Revival style and "a return to classically-inspired symmetry." The nomination form describes this firehouse as in the Francis I style, named for the 16th-century French King who was a patron of the arts during the Renaissance. Despite leading France, the King always seemed to have an obsession with Italy, which explains why the firehouse looks a bit like an Italian villa with a highly residential feel. The nomination form reports that some of the grandest homes in Hoboken were later designed to look quite similar to this station: "The Francis I style and the selection of light materials echo several of the Castle Point Terrace mansions that were constructed in the early 1900s, as such was a forerunner of this stylistic preference in Hoboken." The arrival of European immigrants to Hoboken around this time also likely contributed to the popularity of this architectural style.

The elegant design likely served another purpose, coming as it did near the height of the Reform and City Beautiful Movements. Civic leaders and the wealthy were interested in public order and exposing the working classes to arts, culture, light, and greenery. The nomination form states, "The style chosen for the building reflects a conscious effort to interject a distinguished, unique type of municipal building in a pre-existing neighborhood of tenements and manufacturing sites."

Charles Fall's firm, Fall & Maxon, was called upon to design the station, which includes the following distinctive architectural features:

Walls of tan brick laid in a stretcher-bond. A limestone band runs horizontally across the facade between the first and second stories and terminates in a foliate design.

"The centrally located fire engine door is set in an elliptical arch, set off by a decorative keystone. The engine door is flanked by an equally-sized door to the south and a window to the north."

The rectangular lintels of the door and window each feature cast-stone shields

"A denticulated band in limestone forms a cornice above the second-story level, and the vertically-ribbed copper mansard roof is flanked by parapets with ornamented chimneys."

"The dormer is capped by a triangular pediment also set off by quoining."

"The alleys flanking the building retain their original iron gates and ornamental arches."

Unlike the decommissioned station on Park Avenue, "this free-standing firehouse is set apart from the neighboring four-story brick rowhouses by its style, scale, and materials," yet "captures a residential character with its mansard roof, dormer windows, and ornamented chimneys."

The nomination form posits that this firehouse could have been added to the NRHP alone due to its significance: "As an example of this revival style, it is quite noteworthy, as it heralded its popularity, which reached its height in the years before WWI in Hoboken. The quality of

craftsmanship and design, as well as the degree of intactness, contribute to its importance as a Hoboken firehouse."

Engine Company #6

At the corner of Clinton and 8th streets stands Hoboken's only Classical Revival-style firehouse, built in 1907. Early American public buildings, such as the Capitol, White House, banks, mints, and museums, were all designed to resemble ancient Greek or Roman temples.

Hoboken's firehouses had always been built in line with popular design styles of the time, and the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago had reignited interest in the Classical Revival, which would remain strong for decades. Though much newer than the Capitol or White House, the 1935 Supreme Court Building, designed by Cass Gilbert, looks just as much like an ancient temple as the other two, if not more.

This fire station would also look much more like a temple if it had not lost its cornice sometime around 1980. The area where the cornice once stood is now a bland block of stone or concrete that has severely damaged the building's architectural integrity. Even so, there are still several Classical Revival features remaining, including:

"The basement story features bluestone foundation trim and two courses of rough-hewn limestone which support a smooth stone sill. This forms the base of a rusticated limestone ground floor."

Building materials of "red brick with limestone trim"

"The arched opening for the engine door is centered on the principal Clinton St. facade. The engine door is flanked by a window to the south and a door to the north. Both window and door are of equal height and filled with multipaned square art glass transoms."

Those art glass transoms have been painted over and, today, are barely visible.

"Above the engine door is a grouping of three windows. The central one is wider than those flanking it and has casement windows. These have keystone lintels and art glass transoms as well"

"The central window grouping is framed by two Ionic pilasters with 10" bases. The capitals have garlands below each of the volutes." These Ionic pilasters once supported a metal cornice, but that was removed around 1980, severely compromising the building's architectural integrity

A closer view of the Ionic pilaster capitals and the garlands below each of the volutes

"A stone entablature between the second and first stories bears the 1907

construction date and "Engine Co. No. 6, H.F.D."

"It retains its wood fire tower, which is set back from the facade so as to be hardly visible from the Clinton St. side." It is better viewed from the 8th Street elevation, shown here

The nomination form describes the building overall as "diminutive," "compact yet impressive," and a "good representation of the Classical Revival style." It's also the only Classical Revival firehouse in Hoboken and one of the city's few buildings of that style. Even so, later alterations to the station so degraded its architectural significance that it could not have been listed on the National Register alone. Instead, it stands proudly among its fellow stations in the Multiple Property Submission. The station is still in use today.

Engine Company #3

This grand Italian Villa-style firehouse on the corner of Jefferson and 2nd streets is the newest of the historic stations. It serves as the headquarters building of the modern Hoboken Fire Department. It was built in 1915 and designed by the architectural firm of Fagan & Briscoe. Standing three stories tall plus a tower and occupying an entire corner lot, the station "has the most imposing scale of the firehouses," which "exceeds those built previously, and is influenced by the automobile in its proportions." Its defining architectural features include:

A foundation of rusticated limestone with a high basement

Segmentally-arched engine door apertures on both Jefferson Street...

...and 2nd street facades

Above the first story, the station is primarily faced in beige or yellow stretcher bond brick.

"A limestone balcony with stone balustrade runs the width of the principal facades and is supported by pronounced stone brackets."

"Decorative brick medallions are set into the spandrel panels between the second and third floors."

"The third-story window bays are segmentally arched with prominent keystones."

"Limestone coping and bands courses accentuate the roofline." The nomination form tells of a removed denticulated cornice, which appears to have been added back. A balustrade above the cornice seems to have been completely removed as well.

"Italianate tower and Spanish tile terra cotta roof is suggestive of a belvedere with its balustraded balcony and modillion cornice"

The second street facade is identical to the Jefferson Street side, with all of the same major features.

One of the most notable alterations to the building was the bricking in of the second-story window openings to reduce their size. The original wide openings were in keeping with the tradition of belvederes in Italian villas, especially when paired with the balcony in front.

The nomination form calls this station "the last of the grand firehouses." Hoboken's firefighting history extends to this building, which now serves as the headquarters of the Hoboken Fire Department. Even the humble fire tower, once a tiny wooden structure placed atop the roof of the original firehouses in the city, survived as a grand Italianate version in this station.

Each of Hoboken's historic firehouses has a history and tells a story. But collectively, along with the Fireman's Monument, they tell a simple and powerful story: one of the brave people who have stood up throughout time to keep the city safe from the danger of fire. Hoboken, as it physically stands today, would not exist without them.

This post is dedicated to the men and women of the Hoboken Fire Department who work hard every day to keep their beloved community safe.